Compared to the rest of Robert Siodmak’s filmography, little ink has been spilled over Cry of the City. The most oft-repeated anecdote about the film is that Siodmak himself, while tasked to film a not insignificant amount of the film on location in New York, felt somewhat out of his element. Such discomfort is hard to trace, as even within in the on-location photography, Siodmak’s much more characteristic stylized expressionism is evident. It’s as pleasing to the eye here as it is in his more celebrated efforts, if not moreso in that it is used to depict a noir that carefully withholds the (quasi) genre’s more schematic conventions. Devoid of elements like a seductress, a big score, and a pat moral conclusion, Siodmak punches well above his weight.

Martin Rome awaits pensively in his hospital bed for surgery following his murder of a policeman. He recieves a series of visits, first from a priest, then briefly by his girlfriend Teena. Detectives Candella and Collins follow through with a litany of questions. Bringing up the rear is W.A. Niles, a crooked lawyer, who uses Rome’s compromised position to convince him to confess a jewel robbery that will absolve a client of his. Rome, essentially left for dead, sets out to escape and reconnect with his family – including his devoted Mama Roma and his younger brother, Tony, who sees him as a hero. Detective Candella, considered a family friend by the Rome family matriarch and a pig cop by the rest of the family, uses his emotional proximity to track Martin’s next move.

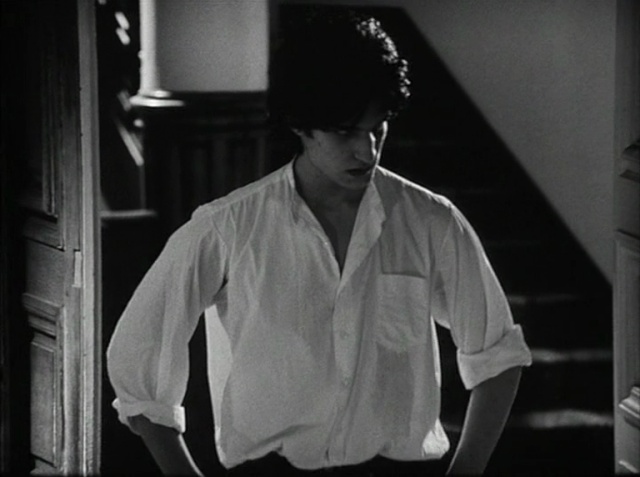

Just a few months ago, when my own personal Noirvember was in full swing, I spent some time with Joseph H. Lewis’ The Big Combo. A perennial favorite of noir enthusiasts, I found it to be less than the sum of its part. While I admire filmmaker Lewis for efforts like Gun Crazy and My Name is Julia Ross and am always a fan of John Alton’s photography, I found it a sort of a middling affair. I think Cornel Wilde’s short-tempered milquetoast hero played a large part in this. Wilde channels an irritable blandness in the film that relies on the lineage of the genre’s history to do the heavy lifting. He comes especially unpleasant in that film because he acts the hero to Richard Conte’s delightfully sleazy villain. I bring all this up because Conte once again delivers the good here, but in this case, he’s given a much more fascinating and rich role to bite into. While superficially he’s the villain again, Siodmak much more convincingly blurs the binary between him and the would-be hero, Detective Candella played by Victor Mature.

Mature gives one of his most subdued performances here as Detective Candella, a role which could easily have benefitted from a certain level of cigar-chomping. As it is, Conte’s Martin Rome tends to steal the show, but Mature has a brilliant understatedness here that brilliantly plays off of Conte. While film noir often provides us with “morally amibigious” heroes, Siodmak does us a further layer of deception, and tries his best to muddle just which of these men are our protagonists. Neither of them are deliberately brought down the rabbit hole of hard luck by a femme fatale. If anything, it’s Conte himself who is the schmoozer, who is often able to talk his way into women supporting him rather than the other way around. For someone who has seen their fair share of noirs, it’s sort of refreshing how the most prominent women here are two burly and middle-aged strongwomen – Betty Garde and Hope Emerson.

The understated dramatic nature of the narrative is refreshing enough on its own, but of course Siodmak provides a robust dynamic energy in each frame. With all the on-location shooting and the mild poetic evocation of Italian-American family life, it feels as though Fox brought Siodmak over from Universal to make a “gritty and realistic street film” which he successfully turned in, but he did of course with his own type of controlled set-bound artifice. The result is the best of both worlds, he captures some of the street-level authenticity that Jules Dassin sought with The Naked City released the same year. Yet, he doesn’t have to sacrifice any of the visual splendor in doing so. The film’s closing sequence of a cold, damp street is one of the most stunning visual sequences in Siodmak’s entire career. It’s clearly the product of studio work and yet, within that, Siodmak captures his own tactile piece of street poetry. It’s a fitting description for Cry of the City as a whole, as well.